Yerba Buena settlement in the early 1840s, from the Society of California Pioneers

I’m kind of a big Carl Jung guy. Not so much because I think he was right about stuff in the scientific sense, but more due to an aesthetic attachment. I like that he went up against Freud (although I like that dude, too) and was willing to face ejection from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society for it. Synchronicity. Archetypes. Individuation. Meyers-Briggs. Maybe I like these things because they’re not scientific.

And even though I never really bought into his idea of the collective unconscious, I was nonetheless intrigued by the stated thesis of Charles A Fracchia’s new book about San Francisco history, When the Water Came Up to Montgomery Street. He had me invested from the introduction:

I have maintained for some years that San Francisco’s history – to our present time – is compounded from the Gold Rush experience, that its distinctive – one might say unique – urban response is situated in what Jung called the collective consciousness… A city that prides itself in its cosmopolitan features, its tolerance, and its penchant for inclusivity, San Francisco continues to operate based on an ethos that was created during the Gold Rush, when the city was composed of a melange of races and nationalities who had simultaneously arrived in the city, producing a melting pot of customs, religious practices, socio-economic and regional differences, and forcing, more or less, a “live-and-let-live” environment.

The difficulties involved in being a resident of San Francisco during the Gold Rush were no less than a birth trauma as Fracchia puts it, an experience that, while not remembered by the matured being, nonetheless is a form of distress as formative as any other in explaining the being’s development.

I don’t know if Fracchia is familiar with another of Freud’s ultimately purged peers, Otto Rank, but his theory of the birth trauma would have been an even better metaphor for explaining “San Francisco values” than Jung’s collective unconscious.

In any case, the book doesn’t really attempt to use the concretes of the Gold Rush to support the thesis Fracchia clearly states in the introduction. I don’t think there is any further mention of the thesis, in fact, and instead his histories all point to the suddenness of SF’s transformation from a trading outpost to a metropolis. I suspect this is related to his statement at the end of the introduction that his thesis isn’t “empirically provable.” Don’t get me wrong, it’s a great read, and the photos and illustrations are fantastic. But the book leaves Jung, the collective consciousness, and the birth trauma on the roadside early on, and I wish it hadn’t.

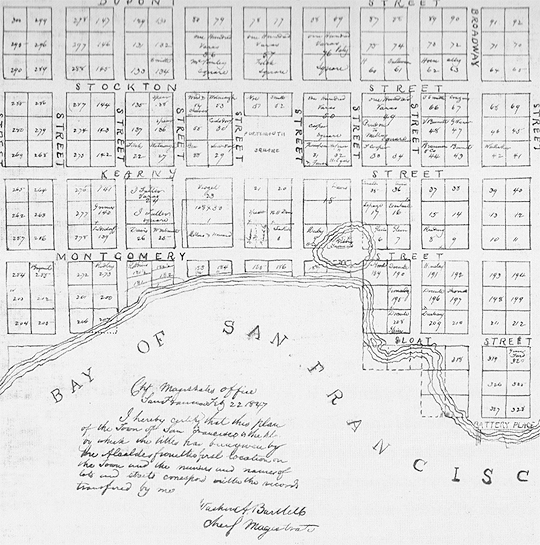

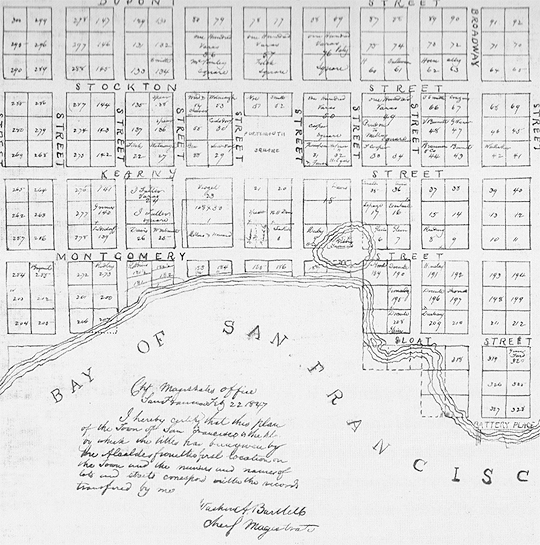

The Bartlett Map of San Francisco, from the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscripts Library, Yale University

The dominant impression the book left on me is one implied in its title. The focus on Yerba Buena Cove, and especially the multiplicity of images of the original eastern edge of the peninsula, has given me the feeling that I know how that part of the city has changed since it was called “Yerba Buena.” Do I really? That’s impossible to prove empirically.

Low-res images in this post were scanned from Charles A. Fracchia’s When the Water Came Up to Montgomery Street.